JOURNEY FROM HONG KONG

In late 1937 my father, a Major in the British Army, was posted to Hong Kong as

second-in-command of the Royal Engineers with an honorary rank of Lieut. Colonel.

The four of us, Father, Mother, my brother Charles and myself,

travelled by ship eastwards from England, through the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal

and

across the Indian Ocean to Singapore, thence north to Hong Kong, arriving there either in

December 1937 or the following January. We spent the next eighteen months on that edge of

China until world events

forced the family apart. In June 1940, because of growing concern about the intentions of

the

Japanese forces then occupying much of China, including the part across the border of the

Hong Kong leasehold, my mother, brother and myself, as well as some 1500 other non-essential

British personnel, were evacuated from Hong Kong.

This account, by my mother, of our

travels and travails was given as a talk to the Broughshane Women's Institute some years

after the end of the The Second World War.

The attitudes and opinions she expresses were quite normal for her class and times. The

little editing I have done was solely on technical grounds.

HONG KONG

On the 29th June 1940, 1500 women and children received notice to leave Hong Kong.

Now, Hong Kong proper is a small island, about 7 miles long and 4 miles across at its

widest point, very hilly and rocky, with very little soil, so practically no

cultivation can be carried out and all food has to be imported. It is therefore

very easy to blockade. [for a map of Hong Kong, go to:

MAP of HONG KONG].

The population at that time, made up of all nationalities,

including a large number of Chinese refugees from the mainland, was about 2 million,

quite a lot to feed.

Furthermore it was just after Dunkirk, there was a large number of Japanese troops on the

other side of the border on the Chinese mainland, who might have thought this a good moment to

attack.

So the evacuation of all (non-essential) women and children was ordered, excepting single and

childless married women who were doing special jobs.

We were told we were to go to The Phillipine Islands and that we could take one trunk per adult,

one suitcase per child, and a small case for immediate use. It was difficult to know what to

pack, the general opinion being that we would probably spend two or three weeks in the

Phillipines and then return. But there was always a chance that we might go elsewhere so I

put in a few warm clothes just in case. How differently I would have packed had I known we

were leaving for ever.

However we all got packed somehow and on the 1st July were herded onto a liner called, of

all names, "The Empress of Japan". This ship was designed to hold 600 passengers, so with

1500 on board there was a bit of a crush. Our 4-berth cabin held 9 women and children, but

some of the other cabins were even more crowded. There were no stewards or stewardesses and

very little in the way of crew and in the dining room it was all help yourself. The heat and

smell were terrific down there so during the 2 days and nights we spent aboard I would grab

a tray with hunks of bread and greasy stew,or whatever there was,and settle down with the boys

on the corridor floor to eat the meal. There was no where else to sit as every available

space was filled with camp beds. Just to help, there was a small typhoon blowing and many

people became sea-sick so the ship was very soon in an awful state.

THE PHILLIPINES

[For a map of of central and north Luzon, go to

PHILLIPINES MAP. San Fernando is north of Manila and Baguis is very close to Bontoc,

northeast of San Fernando.]

We reached Manila at last and found quite a crowd assembled to watch our arrival. I

felt like something out of a zoo as I struggled off the ship with the trunk, 2 small boys and

an assortment of bags, thermos flasks and toy rabbits. Once we got ashore it wan't so bad as

the American red Cross took charge, relieved us of our burdens, and shepherded us onto waiting

buses that took some families into camps in Manila and othres to the railway station. We were

in the latter group and found a special train waiting to take us up to Baguis, a hill station.

There was also a small seaside place available called San Fernando where 36 of us could go, and

we were able to go there. The American Red Cross looked after us very well; they had turned

one coach into a sort of HQ-canteen-information bureau. We were all given a packet of

sandwiches and there was also milk and Coca-Cola and even whiskey for those in need of it.

The train journey lasted about 8 hours and then we were bundled out onto a gloomy platform and

into lorries with wooden seats and canvas covers. There followed another journey through the

dark and rain till finally the few lights of our destination showed and we could hear and smell

the sea.

In this camp there was one main building, an annex and 2 or 3 cottages, in one of which I found

myself and the boys together with a friend and her boy. The buildings stood at one end of a

lovely bay with mountains to be seen in the distance; a beautiful spot altogether.

Being in the middle of the rainy season it was very warm and damp and clothes were rather a

problem as we still had only the one small case of necessities. We all looked rather grubby

and crumpled by the time the rest of the luggage arrived nearly 2 weeks later.

Shoes were another problem as most of us had only the light canvas shoes we'd set out in and

there were no paths. So we mostly went barefoot with the mud squelching up between our toes. We

bathed most days in the bay in some of the oddest garments as few of us had found room for a

bathing suit.

The cottages were built mainly of bamboo with slatted bamboo floors rasied a couple of feet

above the ground. This made cleaning easy and you'd see a smiling Phillipine maiden busily

pushing half of a hairy coconut husk up and down the floor with one foot, causing all the dust

and rubbish to fall to the earth below. This also made a fine hiding place for mosquitoes.

After 2 weeks we were sent up to Baguis where we lived in Camp John Hay, a military holiday

camp.

There was nothing very special about the town of Baguis except the market where the local tribe

of Igorot Indians displayed their goods for sale: handwoven materials, pottery, leather

articles and food. We couldn't afford to buy much as the rate of exchange, 4 pesos to the

pound, was very unfavourable; the peso didn't seem to be worth more than 2/6, one eighth of a

pound. We soon became used to seeing the young braves walking about town clad in loincloths,

feathers and beads. One evening we were even invited to watch some of their dances; this was

a great thrill.

On to AUSTRALIA

It was here that we were told that we'd be going on to Australia as our final destination, and,

after a month in Baguis, we went back to Manila to embark. This second sea voyage took 13

days and was quite uneventful and not so crowded as the previous one. Owing to war-time

secrecy we never knew quite where we were, but we must have passed between Borneo and New

Guinea, over the Equator and onwards until at last Australia hove into sight.

Brisbane was the first stop and a few families who had relatives here disembarked. Two

officials from the Tourist Bureau came aboard to arrange accomodation for the rest of us in

Sydney, Melbourne and Tasmania. We had a day in Sydney and spent most at a beautiful zoo on

one of the harbour island. Here there was an aquarium, full of weird and wonderful fish as well

as, in a pool, an extremely sinister-looking shark.

TASMANIA

My friend and I had decided to go on to Tasmania and, as only one other family had decided to

go this far, our situation was a lot less crowded than it had been when we were 1500-strong.

We left the ship at Melbourne, transferring to a smaller ship that took us to Launceston.

Here the Press were waiting for us; we were lined up on the quay and photographed, looking

rather like scarecrows (In the illustration, I'm on the far left, the boys just to my right).

My friend and I had decided to go on to Tasmania and, as only one other family had decided to

go this far, our situation was a lot less crowded than it had been when we were 1500-strong.

We left the ship at Melbourne, transferring to a smaller ship that took us to Launceston.

Here the Press were waiting for us; we were lined up on the quay and photographed, looking

rather like scarecrows (In the illustration, I'm on the far left, the boys just to my right).

Arrangements had been made for us to go on to Hobart, the capital. Here we spent

3 months in a boarding house. Members of the Victoria League, which somewhat resembles the

Overseas League (in Britain) were very kind to us, inviting us to their meetings and to their

houses, so we came to know quite a lot of people there.

The boarding house was a good one and

we were very comfortable there, but there was one strange thing about it. My bedroom was in

the annexe with one boy sleeping in my room and the other in a small room next door. Whenever

I was in that room at night a feeling of great depression would steal over me and by morning

this would be very bad. Eventually I asked if I could change my room and we were soon moved

back into the main house where the atmosphere was much happier. Later I mentioned this to a

friend and was told that the annexe was a much older building and had been built by convicts.

Some particularly wretched person must have had a hand in its building. Many Tasmanian

families are descended from convicts and some are still touchy about it, but there is no stigma

attached to it now and, after all, some people had been convicted and deported to Australia for

very minor offences. One of the old prisons still exists at Port Arthur and is reputed to have

a very grim and gloomy atmosphere, so we didn't pay it a visit.

Hobart is beautifully situated at the foot of Mount Wellington, from the summit of which one

has

a beautiful view of the surrounding countryside. There are a great many orchards and soft-fruit

gardens as the climate is temperate, but it can get very cold in Winter and even on the warmest

day one needs to have a woolly jacket handy, as every day, at about 3 o'clock, a cold breeze

straight from the South Pole, springs up.

After three months we moved across to the small town of Ulverston, on the North coast. Here the

coutryside has a very English appearence with small fields, green hills and woods. Inland,

however, as well as down the West coast, is very wild and rugged and sparsely inhabited. Here,

in some cases, evolution has stood still and we saw freshwater shrimp that seemed to resemble

exactly their fossilised forebears. The Duckbill Platypus is another strange inhabitant, also a

small cat-like animal called the Tasmanian Devil. The last Tasmanian Aborigine dies a good many

years ago. They were a very primitive race who wore no clothes at all. Their only shelter from

the bitter winter winds would be a sort of a hut formed by propping a few branches up against a

tree.

The accomodation in Ulverston was not good, and we lived in a small commercial hotel near the

(railway) station. At the back was a dark and cheerless room called "The Ladies' Private"

where a man could drink a glass of Port with his lady friend. It was here that we rigged up

a Christmas Tree and the staff, who did not appear to have seen such a thing before, were

lost in admiration when we lit the candles(!). We spent most of the time at the beach, which

was about three miles long with lovely golden sand and rock pools full of anaemones at low tide.

After 2 months here, we moved to Launceston, ready to move to the Australian mainland as we did

not want to be marooned in Tasmania should trouble come. Also we found the Tasmanian Winter

to be very cold. We were 6 weeks in Launceston, spending most of the time nursing the boys

through the Whooping Cough, not a very popular complaint for hotel dwellers.

OUR FIRST AEROPLANE FLIGHT. ON TO AUSTRALIA

After much discussion we decided to settle in or near Adelaide, in South Australia, partly

because it was not too large, and therefore likely to be more friendly, and partly because of

all the fruit that we had heard was to be had there. I'd made up my mind to go by air, some-

thing I'd always wanted to do. Living was cheap and I'd saved enough for the extra fares. As

the day of departure approached the weather got steadily worse and when we took off there was

a 50 mph gale blowing. Never had I imagined that one could be so shaken about; up, down and

sideways with sudden drops for added variety. My older boy (moi!) thought it great fun for a

while till he was suddenly overcome with airsickness and retired, for the rest of the flight,

into a paper bag. The younger boy, who was only six, was terrified, so Mother had to be very

brave, making delighted cooing noises with every bump and exclaiming how lovely the whole

experience was, all the while taking fearful peeps at the rocky mountains and, later, the

raging seas, far below.

That cured me of ever wanting to fly again, even though the second half of the trip, from

Melbourne to Adelaide, was as calm and quiet as one could wish. there was a thick band of

cloud below us all the way, and a sthe sun sank lower we seemed to be flying through a

fairyland of rosy hills and valleys, castles and turrets; it was all very lovely. Night had

fallen by the time we reached Adelaide a fairy land of twinkling lights that we saw below us.

We had covered the 8-900 miles in about 8 hours; my friend, who had opted to come by sea and

land travel, took about 48 hours.

SOUTH AUSTRALIA

We found Adelaide to be a very pleasant city, laid out in a square, and bounded onn each side

by a Walk between lawns, bright flower beds and shady trees. The suburbs stretched out in all

directions, served by trams, buses and electric trains. In the background are the Mount Lofty

maintain ranges. the sea is about 8 miles away and there are many small towns and villages

along the coast with such familiar names as Brighton and Hove. The area is a great place for

wine and there are many vinyards at the foot of the hills. One could buy a half-gallon flagon

of a good sherry for 5/6 (about 28p UK). A lot of celery is grown there also, most of which

ends up in the Melbourne and Sydney markets. And as for the fruit, well we certainly had not

been misled about that! Nearly every garden has its orange and lemon trees, also apricots,

peaches, nectarines, figs, plums, etc., and of course, grapes of every variety. One soon

learns to scorn anything but the black or white muscatels. We learned to make our own sultanas,

by dipping bunches of grapes into a boling solution of caustic soda (lye) for two or three

seconds, then drying them in the sun on wire netting, protected from birds, flies and ants.

The summer was too hot and dry for the soft fruits but one didn't miss them as so many other

kinds were available.

Except in the actual towns and villages, most of the houses are one-storeyed bungalows with

wide, shady verandas to keep out the fierce summer sun, and gardens bright with flowers and

green lawns that daily have to be well watered during the summer. When the summer temperatures

start to rise the grass withers and dies and the whole landscape turns to a browny yellow, but

it all springs up again when the winter rains come.

All through the summer, from November to

March, the daily temperature rises and falls. It would reach 110-112F in Adelaide on the

worst days and I have seen it hit 118F further inland. The temperature may stay high for

several days, then suddenly the wind will change its quarter and blow cool instead of hot with,

perhaps, a shower of rain and you thinkthat this is thwe most wonderful thing that has ever

happened. After a bit, though, back comes the heat and you shut all the doors and windows and

pull down the blinds, which all helps to keep the house cool. Then, on some days, a hot north

wind will bring a fine red dust from the interior, where there has been a great deal of erosion

due to droughts, overstocking, and too much felling of timber. This dust penetrates everywhere

and settles all over the house, and if you have to go out you come back looking like a Red

Indian a s the dust sticks to your hot face. the day is darkened, lights are turned on and

the traffic crawls along with headlights on. Then the wind drops and so does the dust and

everyone starts spring cleaning.

The winters in South Australia are usually very pleasant, not too cold and with plenty of

sunshine most of the time. Occasionally I saw ice on a puddle or frost on the grass, but that

was all; none of the snow and hard frosts we have here.

The men wear their dark suits in summer and winter alike in the cities. Light suits need

frequent cleaning or laundering and most housewives have their hands full enough without adding

2 or 3 suits to the weekly wash. Domestic help of any sort is extremely scarce and housewives

in all walks of life do their own work. Most of the menfolk are well trained in domestic duties

from childhood and I have eagtedn many good cakes and pastries made by the man of the house.

The Australians are a very friendly, warm-hearted people, and I met with nothing but kindness

during the 4½ years that I lived among them. they are also outspoken, very independent,

and have a genius for improvisation, that must have descended from the earliest settlers who

had to do so much of it. They are also exceedingly loyal and take the greatest interest in the

affairs of the "Old Country" and particularly in the Royal Family. I can imagine the terrible

disappointment that must have followed the announcement postponing the Royal Tour. Most

Australians seem to have an ambition to visit the U.K. and it is surprising many of them manage

to do so. I knew a man and his wife who had a little greengrocery shop and they had made the

trip several times! Each time they would set up shop in a different part of England until

they'd saved enough money to get home again. They were contemplating making another trip after

the War had ended, and I still wonder sometimes whether they managed it.

A great deal has been done by irrigation systems from the Murray River and along its banks at

the town of Remark are laid out great groves of Orange trees the fruiit of which are exported as

well a sold locally. I took the boys on a trip up the Murray in a little paddle steamer that

carried about 20 passengers. It was very pleasant but the scenery was rather monotonous:

willows on one side, cliffs on the other. This is a feature of the Australian scenery: it can

go on and on for a many, many miles.

At one spot on the river bank there was an Aboriginal settlement, and we all went ashore for a

visit. It was a rather sad and pathetic place; they are a dying race, usually of poor physique

and low mentality, and will one day cease to exist, though the Government is doing all it can

to help them. With the coming of the white races to Australia, the conditions under which the

Aborigines lived gradually and unavoidably changed and now many of them, are living in these

settlements. In the Northern Territories they seem to be a better breed and still lead a

tribal life.

My friend, Jill, and I did not wish to live in Adelaide itself, so we settled down in the

seaside suburb of Glenelg, first in a boarding house and finally in a trented house, right by

the sea with only a footpath between us and the sandy shore. It was an ideal spot for the boys

who spent many hours on the sands and in the sea. Luckily our area wasn't shark-infested like

Sydney, where every year one or two people are taken, sonmetimes in quite shallow water, and

where watchers are always on the look out to sound the alarm when a shark is sighted. A shark

was sighted once or twice near the Glenelg Pier so we never went very far from shore and always

kept a good look out for any shadowy shapes.

I knew very little about cooking in those days, but Jill was very good at it and taught me many

things so that we were soon able to take turns cooking the dinner. However, neither of us had

previously done much laundry work, so we had to call in a neighbour to show us how to use the

"Copper" with which all Australian houses are provided. This was in a small wash house,

with trainwater laid on from a big galvanized iron tank outside. there was a tap from the

mains in case the tank emptied before the next rainfall. By the end of my stay I was doing the

whole weekly wash for five people and oftyen visitors as well. Quite a change from Hong Kong

where even my stockings had been washed and darned for me!

WWII AND AUSTRALIA

In December 1941 came the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and Hong Kong, and on Christmas Day,

Hong Kong surrendered. The first news of my husband didn't come until the following August

when I heard that he was a POW. A year after that the first letters began to arrive. (A

typical Japanese trick: anything to annoy you.)

All these events had brought the war closer to Australia and very soon a blackout was ordered

for all coastal areas, and we received instructions to be followed in the event of the coast

being evacuated. Every child had to wear an identity disc and carry a first aid outfit in its

school satchel. The Japanes invasionm fleet came very close to North Australia, but was beaten

off and destroyed in time. Darwin was bombed and a midget submarine penetrated Sydney harbour.

It too was destroyed and the remains were later exhibited in various cities. I have a small

portion of it as a souvenir.

By this time I'd joined the Red Cross and was doing various jobs in connection with it. the

most interesting was at the Blood Bank where I worked 2 or 3 days a week for 2 years until it

closed down. We took about 20 donors a day and collected up to a pint of blood from each into

special vacuum bottles.

The blood was then taken over to a close by hospital laboratory where it was

put through a seperator; the clear yellow serum running into special bottles and the red waste

into a bucket. the serum would then be frozen and furthervtreated so that it ended up looking

like fine yellow bath salts. In this state it would keep for a long time and large stocks

could be built up. Much of this was flown to New Guinea and other places where there was

fighting going on. It helped save many lives.

the donors were of all sorts and kinds; men and women, young and old. Some came

regularly, every three months. the most amusing were four undertakers who always came together

and were the most cheerful people imaginable. they would lie in their cubicles, shouting and

joking with each other so that soon the entire building would be ringing with laughter. It was

always very cheering for the more nervous of our new donors.

Another job was in the canteen for the almost-recovered patients in a military camp, where we

also took library books around some of the wards. Many of the patients would be busy weaving

scarves on tiny hand looms, or making felt toys, slippers, handbags or string belts and would

say they had no time to read. Yet another job was in the Convalescent Home for Service Men in

Glenelg, where the Red Cross Aids, as we were caleed, did all the bed-making, ward-sweeping,

and meal-serving to the men, with Matron keeping a strict eye on everybody, and woe betide if

the blankets weren't tucked in just so!

For a short time I worked in the Home for Incurables, where they were always understaffed. Here

I washed and generally tidied up some half-dozen old men, helped clean up the ward, sort linen,

serve meals, and feed those who were helpless. Red Cross Aids were also expected to attend

lectures and pass examinations in Home Nursing, First Aid and A.R.P. so there was never a dull

moment.

Once, I spent 2 weeks on Kangaroo Island, which was about 6 hours by sea from Adelaide. It is

quite large, about 90 miles long and 30 wide, but very sparsely inhabited. One could go for

many

miles through the bush without seeing anybody at all. There were no bus services, but the mail

van made a round of the nearer homesteads once or twice a week, delivering and collecting

goods and mail. Just about anything was liable to be pushed in amongst the passengers, though

livestock would be consigned to a rickety trailer behind the van. The one time we went on this

ride, it was dark before we'd made our last call, but the moon was shining brightly, whic was

just as well because the 2 pigs that we were supposed to pick up had escaped and it was over an

hour before they were finally caught, with shouts and squeals amongst the trees.

The island has some really lovely bays and beaches, on one of which I was lucky enough to find

a paper nautilus shell. These shells are quite rare and it is a mystery to me how they can

stand being washed by the waves up and down sandy beaches without disintegrating. The fish

within the shell sets up a little sail and it can then travel quite long distances on the

surface.

It was also during this visit that I saw my only kangaroos, 2 big fellows bounding across the

road in front of us. They are protected now, having been hunted to near-extinction for the

sake of their tails which make, so I am told, a very savoury stew. The baby kangaroos are

usually known as joeys and you may have wondered how trhey get into their mother's pouch.

Well, it goes something like this: The joey is born in the usual way when it is only 2 or 3

inches long, and then it climbs slowly and painfully up it's mother's furry tummy until it

reaches the pouch. Inside, there is a single teat to which the newborn attaches itself, and

there it stays until it is old enough to sit up and take notice. During the initial climb,

the mother sits upright and perfectly still, making no attempt to help. Experiments have

shown that the baby will always climb straight up, so that if the mother moves or changes her

position the baby might miss the pouch and soon die of exposure.

One thing I missed in Australia was the changing of the seasons. Most of the trees are gums,

which shed their bark but not their leaves, so one never sees the fresh, young green of spring

or the leovelt colours of autumn. Adelaide is famous for its almond blossom, however, and

there are whole orchards of almond trees, as well as many others growing in the hedgerows

around fields, so that this is one wonderful sign of spring.

Food and clothes rationing were introduced in to Australia during 1942, but neither were as

severe as in Britain. Meat, butter, sugar and eggs were the only foods to be rationed and

since allowances were twice as much as in Britain today (1947?) it was no great hardship.

Except for the meat, of course. Many Australians are heavy meat eaters and will take it 2 or 3

times a day often with a poached egg perched on top if it is a steak or chop. Sweets (candy)

were not rationed but were very scarce and of poor quality. Chocolate was almost unobtainable

as it was not manufactured in South Australia. Anything not made in your state was very hard

to get as the restrictions on travel and freight by rail were very severe. There was only one

railway line between Adelaide and Melbourne and when crossing from Victoria into New South

Wales one had to change trains because the Australian States had never managed to come to an

agreement on adopting a common railway guage. Every country has its stupidities, I suppose!

THE JOURNEY HOME

Up to the end of 1944 we were strongly advised against applying for a passage home unless for

very urgent reasons. But, early in 1945 that advice was changed and we were almost invited to

apply. I did not need any prodding and a few weeks later the boys and I found ourselves in

Sydney together with many other families, witing to embark. I was sorry to be leaving all the

good friends I'd made, but it was wonderful to be starting for home at last, and, on the 5th.

March, 1945, we steamed out of Sydney Harbour under the famous bridge, each of us clutching the

cumbersome lifebelt that was to become one's closest companion for the rest of the voyage A

sharp reprimand was the fate of anybody caught without one. I was in a 3-berth cabin, while

the boys were in a dormitory with 30 other boys on a lower deck at the other end of the ship.

Not a good arrangement so far as I was concerned, as I felt I would never see them again if

anything happened. However, in a crowded ship in war-time one must take what comes, and we

were much better off than many other ships. There were a good many servicemen aboard as well

as families.

Our first port of call was Wellington, in the North Island of New Zealand where we spent a week

while the ship was being loaded with meat, butter and cheese for England. This is a very windy

city, albeit very attractive too. The countryside around is also beautiful; very mountainous

and green. One day the military and Red Cross people

combined to give us a day's outng up the Hutt Valley to one of their National Parks, taking us

there in lorries (trucks) and giving us picnic meals with icecream and soft drinks laid on. For

the children there were races and prizes. It was a great day and much appreciated.

We sailed onwards on 19th. March and saw no more land until we reached Panama on the 30th. We

had two Wednesdays in one week when we crossed the International Date Line and the clocks were

put back 24 hours, metaphorically speaking of course. It was a very quiet, uneventful voyage

and we amused ourselves in the usual ways with deck games, dances and concerts. There was

morning school for the children followed by half an hour of physical training and, of course,

the inevitable boat drill and inspection of lifebelts.

As we moved slowly into the Panama Docks, the weather was hot and calm, and the bay was dotted

with the triangular fins of sharks crusing around in the oily-looking water and trailing the

ship for scraps. I counted at least a dozen and really hoped that nobody would fall overboard.

We had the afternoon and evening ashore in Panama City but it was Good Friday and everything,

except the cafes and bars, was shut. We looked into a church in a square; all the statues were

draped in black and there was a service going on at one end, but in the middle of the church

it was more like a club with people sitting and chatting to one another, passing to and fro,

the women with black veils thrown over their heads. We walked along hot, narrow streets

through crowds of people of all sorts of nationalities and shades of complexion. In a

restaurant, looking for lunch, we couldn't understand the menu so chose at random and were

presented with a huge mound of savoury rice in which were nestled pieces of fried chicken, and

thought ourselves lucky; it could have been so much worse! At the next table was a stout,

dark-skinned lady wading through a mysterious meal of many small dishes. When she could eat no

more she brought out paper bags into which she shovelled the remaining food to be taken home

and eaten later. I've never seen so many small bars, and remember one in particular, called

"Sloppy Joe".

Early the next moringe we entered the famous Panama Canal, strongly fortified and policed by US

soldiers. US officers and men boarded the ship and kept a stern eye on everybody, for fear we

should be taking photographes or sabotaging something; this made us all feel very guilty!

There were three or four locks at the beginning of the Canal, which looked then more like a

river winding in and out between banks and high wooded cliffs. Later it broadened out into a

large lake full of small islands with the tops of drowned trees, submerged by the damming of

the Canal, showing above the water's surface. At the end of the lake we could see the workings

of a lock and when we were in the lock we could see two more below, like giant steps, leading

down to the sea again and the town of Colon. It was a most extraordinary sensation, being

perched on the top of a cliff in an ocean-going liner!

We didn't stop at Colon, but sailed on up past Jamaica, Cuba, and the Bahamas, to New York;

this

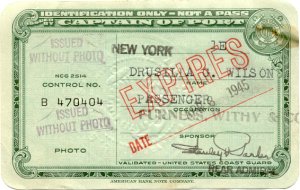

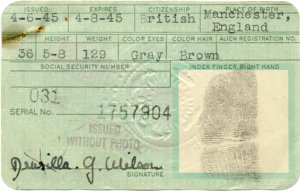

part taking five days. During this time we were each given an enormous questionnaire to fill

out for the benfit of the N.Y. immigration authorities. It demanded full details of one's

family history and asked such ridiculous questions as "Are you an Anarchist?" or "Do you wish

to overthrow the Government?" and we often felt like answering some of these with a large "YES".

We arrived in New York in the evening and saw the Statue of Liberty and the famous New York

skyline; all very impressive. Next morning a hoard of officials swarmed aboard and we spent

the rest of the day queueing up this and that; filling out forms and having our fingerprints

taken, so that it wasn't until 4.30 in the afternoon that we could actually go ashore. I won't

attempt to describe new York to you except to say that we enjoyed our short visit and wished

it could have been longer than the one whole day. We bought a few pairs of stockings, one or

two undergarments, some elastic, a few toys and as much food we could with our small dollar

allowance. As we returned to the ship for the last time the boys spotted a large slot machine

We arrived in New York in the evening and saw the Statue of Liberty and the famous New York

skyline; all very impressive. Next morning a hoard of officials swarmed aboard and we spent

the rest of the day queueing up this and that; filling out forms and having our fingerprints

taken, so that it wasn't until 4.30 in the afternoon that we could actually go ashore. I won't

attempt to describe new York to you except to say that we enjoyed our short visit and wished

it could have been longer than the one whole day. We bought a few pairs of stockings, one or

two undergarments, some elastic, a few toys and as much food we could with our small dollar

allowance. As we returned to the ship for the last time the boys spotted a large slot machine

and decided to invest our last 10 cents in a bag of peanuts. In went the coin, down came the

handle, and out came a cascade of peanuts, sans bag, all over the floor. I still don't know

whether the bag had come apart in the machine or whether we were supposed to have provided our

own. There didn't seem to be any paper shortage as even the smallest purchase came in an

enormous paper bag. It will forever remain one of life's little mysteries.

and decided to invest our last 10 cents in a bag of peanuts. In went the coin, down came the

handle, and out came a cascade of peanuts, sans bag, all over the floor. I still don't know

whether the bag had come apart in the machine or whether we were supposed to have provided our

own. There didn't seem to be any paper shortage as even the smallest purchase came in an

enormous paper bag. It will forever remain one of life's little mysteries.

So far, our ship had sailed alone, but for the last lap across the Atlantic we were to join a

convoy, and I think there were few of us, except for the children (who were all agog for a sight

of the enemy), who enjoyed much peace of mind during the next 12 days. With a pilot aboard, we

steamed slowly out of New York harbour, and, after several hours, met up with the rest of the

convoy, about 40 in all. We then formed ranks, about 8 ships across and 5 deep, with the

steamers

in the front row, and cargo ships and oil tankers behind. We were attended by four Corvettes

that went up and down and around about us like sheepdogs guarding their flock, forever on the

look out for U-boats, E-boats or enemy aircraft. It was quite thrilling to stand at the ship's

rails and watch all these ships travelling together, not very fast as we had to go at the speed

of the slowest ship. At night there wasn't a glimmer of light, but you could feel them there,

all the same.

Two nights out from New York, Charles, my younger boy came down with the mysterious fever that

was

attacking many of the children on board. They could be perfectly well in the morning but have

a raging fever by nightfall. I had my son up in my bunk, his temperature having passed 104F,

and was waiting for the orderly to bring the M-B pills ordered by the medical officer when one

of my friends came in, white as a sheet, and said "Something's wrong; there's a ship on fire."

I think that that was the worst moment of my life! My first thought was "If we are torpedoed

and have to take to the boats, Charles won't live through the night!" for it was a very rough

and wet night out there. Then I ran out onto the deck, which was close to my cabin, and there

was a blazing tanker behind us, lighting up the night; it was a terrible sight, one not easily

forgotten. Still the convoy steamed on, it couldn't stop. Only one of the corvettes went to

help and managed to pick up some of the tanker's crew. Some others had escaped in a lifeboat,

but the rest had been killed in the explosion. Later we were told that the ship hadn't been

attacked, but the ship ahead had developed engine trouble and had fallen back, colliding with

the other in the darkness.

All through those 12 days we were never fully undressed except to have a bath and always kept

emergency bags at hand. Our lifebelts had now been fitted with little red lights to be turned

on if one should find one self in the sea at night. The belt also contained a tin of iron

rations. Full dress boat-drills were held every day and the boats were lowered to make sure

that they were in working order.

We had only that one day of really rough weather and after that it became calm and warm and

really lovely. One morning I was out on the deck, leaning on the rails, watching one of the

other ships signalling ours. I asked a nearby merchant seaman if he could tell me what the

message was. he watched the signals attentivley for a minute or so, then turned to me and

announced in sepulchral tones: "Prunes for dinner again today".

One afternoon, about two days out from England, we were sitting in our cabin having a cup of

tea. (There was a small galley close by where one could always get boiling water. Since tea

wasn't served on board, this was greatly appreciated.) Suddenly there was a strange noise, that

was felt as much as heard, as tho' somebody had dropped some heavy trunks on the deck above.

Indeed, that was what we thought it was as, by that time everyone was busy packing up. A few

minutes later we heard it again, and then the boys rushed in highly excited to say that the

corvettes were dropping depth charges. We all ran out to watch and, sure enough, great spouts

of water were arising from the sea on the far side of the convoy, each followed by a muffled

explosion, while the corvettes were racing around like mad. After a while things quietened

down but the whole convoy was kept zig-zagging backwards and forwards for the rest of the day

and into the night, during which we lay sleepless, listening and waiting. We never knew what

happened, whether the u-boat was hit or how many of them there were. Of enemy ships or planes

we never caught a glimpse, so were really very lucky.

Bye and bye we sighted the Scilly Islands and there the convoy broke up, most of the tankers

turning up the channel to France while we turned north for Liverpool. I was sorry to part

company; the run across the Atlantic had been a wonderful experience and one I wouldn't have

missed in spite of all my fears and tremblings. It left me with nothing but the greatest

admiration for the men of the Merchant Navy.

Return to

Wilson Family Tree

Genealogy Central

My friend and I had decided to go on to Tasmania and, as only one other family had decided to

go this far, our situation was a lot less crowded than it had been when we were 1500-strong.

We left the ship at Melbourne, transferring to a smaller ship that took us to Launceston.

Here the Press were waiting for us; we were lined up on the quay and photographed, looking

rather like scarecrows (In the illustration, I'm on the far left, the boys just to my right).

My friend and I had decided to go on to Tasmania and, as only one other family had decided to

go this far, our situation was a lot less crowded than it had been when we were 1500-strong.

We left the ship at Melbourne, transferring to a smaller ship that took us to Launceston.

Here the Press were waiting for us; we were lined up on the quay and photographed, looking

rather like scarecrows (In the illustration, I'm on the far left, the boys just to my right).

We arrived in New York in the evening and saw the Statue of Liberty and the famous New York

skyline; all very impressive. Next morning a hoard of officials swarmed aboard and we spent

the rest of the day queueing up this and that; filling out forms and having our fingerprints

taken, so that it wasn't until 4.30 in the afternoon that we could actually go ashore. I won't

attempt to describe new York to you except to say that we enjoyed our short visit and wished

it could have been longer than the one whole day. We bought a few pairs of stockings, one or

two undergarments, some elastic, a few toys and as much food we could with our small dollar

allowance. As we returned to the ship for the last time the boys spotted a large slot machine

We arrived in New York in the evening and saw the Statue of Liberty and the famous New York

skyline; all very impressive. Next morning a hoard of officials swarmed aboard and we spent

the rest of the day queueing up this and that; filling out forms and having our fingerprints

taken, so that it wasn't until 4.30 in the afternoon that we could actually go ashore. I won't

attempt to describe new York to you except to say that we enjoyed our short visit and wished

it could have been longer than the one whole day. We bought a few pairs of stockings, one or

two undergarments, some elastic, a few toys and as much food we could with our small dollar

allowance. As we returned to the ship for the last time the boys spotted a large slot machine

and decided to invest our last 10 cents in a bag of peanuts. In went the coin, down came the

handle, and out came a cascade of peanuts, sans bag, all over the floor. I still don't know

whether the bag had come apart in the machine or whether we were supposed to have provided our

own. There didn't seem to be any paper shortage as even the smallest purchase came in an

enormous paper bag. It will forever remain one of life's little mysteries.

and decided to invest our last 10 cents in a bag of peanuts. In went the coin, down came the

handle, and out came a cascade of peanuts, sans bag, all over the floor. I still don't know

whether the bag had come apart in the machine or whether we were supposed to have provided our

own. There didn't seem to be any paper shortage as even the smallest purchase came in an

enormous paper bag. It will forever remain one of life's little mysteries.